Complexity Solutions

Question 1: Tail

What is the complexity of the tail function?

Answer:

The complexity is just O(1). This is despite it returning a list of length n-1. This is because, if the list is x:xs, Haskell can just output xs immediately, without needing to recurse through the tail.

Question 2: Adding an element to a list

Write a function to add an element to the end of a list. What is the time complexity of the function you have written?

Answer:

We give two possible functions below.

addElem :: a -> [a] -> [a]

addElem elem ls = ls ++ [elem]

addElemRecurse :: a -> [a] -> [a]

addElemRecurse elem ls = case ls of

[] -> [elem]

x:xs -> x : (addElemRecurse elem xs)

Both of these have complexity O(n). This is because the concatenation operator ++ needs to recurse through the left-hand side list in order to add the subsequent list.

Question 3: Reverse (++)

We have written the following function:

reverse :: [a] -> [a]

reverse list = case list of

[] -> []

x:xs -> (reverse xs) ++ [x]

Find the complexity of the reverse function above. Is there a better way to implement this? What would be the lowest complexity for the reverse function?

Answer:

At first this function appears to be O(n) as we recurse through the list once. However the ++ concatenation operator itself adds a hidden ‘cost’ to the time complexity as concatenation takes O(n) time. Hence this reverse function is actually O(n^2). A better way to implement this would be to use an accumulator as seen below.

rev2 :: [a] -> [a]

rev2 list = revHelper list []

where

revHelper list acc = case list of

[] -> acc

x:xs -> revHelper xs (x:acc)

This is now O(n), as we recurse through the list once, without using concatenation.

Question 4: Minimum length list

We have written the following function:

short :: [[a]] -> Int

short list = case list of

[] -> error "No lists in the list"

x:xs -> helper (tail(list)) (length(head(list)))

where

helper :: [[a]] -> Int -> Int

helper ls v = case ls of

[] -> v

x:xs

| length(x) < v -> helper xs (length(x))

| otherwise -> helper xs v

Find the complexity of the short function above. Note: assume there are c lists in the list of lists.

Answer:

The complexity is O(mn) where m is the length of the input list and n is the maximum length an internal list. This is the best worst case complexity that can be achieved.

Sorts

All implementations can be found here.

Question 1: Standard Sort

Above, we defined insertionSort. What is its complexity?

Answer:

Its complexity is n^2, as each element needs to be inserted and at worst you will need to go through the whole list to insert it:

0 + 1 + 2 + ... + n-1 = n(n-1)/2 = O(n^2)

Question 2: Mergesort

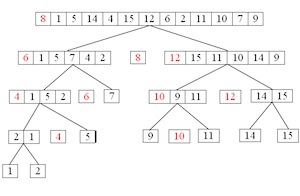

Conceptually, mergesort works as follows:

- Divide the unsorted list by halving the list until there are

nsublists of1element (an element of1is considered sorted). - Repeatedly merge sublists to produce new sorted sublists until there is only 1 sublist remaining. This will be the sorted list.

Here’s an example of how it works:

Implement the mergesort algorithm in Haskell, if you can. Using this function or otherwise, determine the complexity of the algorithm.

Answer:

Here is a mergesort implementation:

mergeSort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

mergeSort ls = helper (makeIndividualList ls)

where

-- Initial Split Into Single Element Lists

makeIndividualList :: [a] -> [[a]]

makeIndividualList ls = case ls of

[] -> []

x:xs -> [x] : (makeIndividualList xs)

-- Merges Two Sorted Lists

merge :: Ord a => [a] -> [a] -> [a]

merge ls1 ls2

| ls1 == [] = ls2

| ls2 == [] = ls1

| (head(ls1)) <= (head(ls2)) = head(ls1) : (merge (tail(ls1)) ls2)

| otherwise = head(ls2) : (merge ls1 (tail(ls2)))

-- Merges Lists of Lists in groups of 2

mergeLists :: Ord a => [[a]] -> [[a]]

mergeLists ls = case length(ls) of

0 -> []

1 -> ls

_ -> (merge (head(ls)) (head(tail(ls)))) : (mergeLists (drop 2 ls))

-- Recurses through mergeList until there is only one list, i.e the sorted list

helper :: Ord a => [[a]] -> [a]

helper ls = case length result of

0 -> error "List is Empty"

1 -> head(result)

_ -> helper result

where

result = mergeLists ls

It has complexity O(nlog(n)). Deriving this result can be somewhat complicated. However, there is an easy method. If we let T(n) be the complexity required to merge sort a list of length n, then we can create the following recurrence relation:

T(n) = 2T(n/2) + n

So to merge sort a list of length n, we first need to mergesort to lists of n/2 and then merge the two, which takes 2n - 1 operations in the worst case (i.e the final element of each list is the one that finishes the merge). If then expand this recurrence relation, we get:

T(n) = 2T(n/2) + n

= 2(2T(n/4) + n/2) + n

= 2(2(2T(n/8) + n/4) + n/2) + n

...

= 1 + 2 + 4 + ... + n/4 + n/2 + n

= nlog_2(n)

Thus, mergesort has complexity O(nlog(n)).

Question 3: Quicksort

Conceptually, quicksort works as follows:

- Pick the first element of the list as a “pivot”

- Reorder the array so that all elements with values less than the pivot come before the pivot, while all elements with values greater than the pivot come after it (equal values can go either way). After this partitioning, the pivot is in its final position. This is called the partition operation.

- Recursively apply the above steps to the sub-array of elements with smaller values and separately to the sub-array of elements with greater values.

Here’s an example of how it works:

Implement the quicksort algorithm in Haskell, if you can. Using this function or otherwise, determine the complexity of the algorithm. Is there a better way to implement this? What are the average and worst case complexities for the quicksort function?

Hint: Use list comprehensions!

Answer:

Here are two quicksort implementations:

quickSort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

quickSort ls = case (small, big) of

([], []) -> [v]

(_, []) -> (quickSort small) ++ [v]

([], _) -> v : (quickSort big)

(_, _) -> (quickSort small) ++ [v] ++ (quickSort big)

where

-- Pivot

(v, small, big) = (head(ls), [ x | x <- tail(ls), x <= (head(ls)) ], [ x | x <- tail(ls), x > (head(ls)) ])

altQuickSort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

altQuickSort ls = case ls of

[] -> []

_ -> altQuickSort([ x | x <- tail(ls), x <= (head(ls))]) ++ [head(ls)] ++ altQuickSort([ x | x <- tail(ls), x > (head(ls))])

They both use list comprehensions to construct the pivots and also the same logic, but the second is neater is how the logic is conveyed (although perhaps more confusing initially).

Quicksort’s worst case complexity is O(n^2). This would occur when either big or small has size n - 1, i.e the head is either the smallest or biggest element, at each step. This means that only one element is sorted at each step. Thus, we get the same sum as insertion sort for how many operations it takes:

(n - 1) + (n - 2) + ... + 2 + 1 = n(n-1)/2 = O(n^2)

This seems bad, but quicksort has a trick. Its average complexity is θ(nlog(n)) (Theta is used for average case). This is because, on average, both small and big have half of the list each. This means that we are halving the list each step, giving us the same recurrence relation as mergesort.

Challenge Question: Bogosort

This one’s an interesting one. Don’t worry if you don’t recognise all the code in here, focus on the conceptual details. Before you do anything, what does this program actually do?

-- http://rosettacode.org/wiki/Sorting_algorithms/Bogosort#Haskell

import System.Random

import Data.Array.IO

import Control.Monad

isSorted :: (Ord a) => [a] -> Bool

isSorted (e1:e2:r) = e1 <= e2 && isSorted (e2:r)

isSorted _ = True

-- from http://www.haskell.org/haskellwiki/Random_shuffle

-- TL;DR it randomly shuffles the list

shuffle :: [a] -> IO [a] -- This is what requires all the imports

shuffle xs = do

ar <- newArray n xs

forM [1..n] $ \i -> do

j <- randomRIO (i,n)

vi <- readArray ar i

vj <- readArray ar j

writeArray ar j vi

return vj

where

n = length xs

newArray :: Int -> [a] -> IO (IOArray Int a)

newArray n xs = newListArray (1,n) xs

-- This new ">>=" symbol can be thought of as simply "stripping"

-- the IO type from the output of shuffle, i.e. making it type [a]

bogosort :: (Ord a) => [a] -> IO [a]

bogosort li | isSorted li = return li

| otherwise = shuffle li >>= bogosort

What are the average and worst time complexities of this program? Hint: Does bogosort ever terminate?

Answer:

Bogosort is entirely random: it randomly shuffles the list, checks if it is sorted and if it isn’t, repeats. This means that bogosort has no guarantee of ever stopping: it could shuffle randomly forever, never accidentally sorting the list. Thus, in its worst case, bogosort has complexity O(∞).

However, this doesn’t mean we can’t analyse its complexity. Bogosort is trying a random permutation of the list each time. We know there are n! different permutations (ignoring repeated elements). Thus, at each step, bogosort has a 1/n! chance of sorting the list. Thus, on average, bogosort has complexity θ(shuffle(n)n!), where shuffle(n) is how many operations it takes to shuffle a list of length n and check if it is sorted (usually n). Note that bogosort has a fantastic best case: n: if the list is already sorted, then bogosort will just return it back immediately!

Bogosort is a very stupid sorting method, but it does show that the complexity depends heavily on what case you are considering: best, average, worst.