Trees

Hard List Problems

We have gotten a lot of use out of lists: we have defined them in a few different ways and used them in many problems. Given this, let’s consider a difficult problem and see if we can solve it using lists:

Problem: We have a biased coin: it has probability h that it shows a head and 1-h that it shows a tail. If we flip the coin 10 times, what is the probability that the sequence will have the subsequence HTHTT. For example,TTTHTHTTHH has the required subsequence but THTHTHTHTH doesn’t.

This is a difficult problem, even without considering the Haskell implementation side. We could try solve it mathematically - MATH1005 to the rescue! - but even then it is difficult…

A more reasonable solution could be to generate all the possible sequences with heads and tails, and then calculate the probability from there. But how can we generate all sequences?

The easiest method would probably be a recursive function like so:

addTerm :: (Char,Char) -> [String] -> [String]

addTerm (a,b) ls = case ls of

[] -> [a:"",b:""]

x:[] -> [a:x,b:x]

x:xs -> (a:x) : ((b:x) : addTerm (a,b) xs)

applyNTimes :: Int -> a -> (a -> a) -> a

applyNTimes n x f

| n == 1 = f x

| n > 1 = applyNTimes (n - 1) (f x) f

| otherwise = error 'Invalid Application Numbers'

nTerms :: Int -> (Char, Char) -> [String]

nTerms n (a,b) = applyNTimes n [] (addTerm (a,b))

This does generate the sequences, for example:

nTerms 5 ('H','T') = ["HHHH","THHH","HTHH","TTHH","HHTH","THTH","HTTH","TTTH","HHHT","THHT","HTHT","TTHT","HHTT","THTT","HTTT","TTTT"]

However, the functions used are quite complicated. We needed 2 recursive functions, partial function applications and more! There should be an easier way…

In fact there is an easier way! Make our own data type that is perfectly suited to the problem!

Tree Data Types

In the question above, each coin flip presents us with two options: either the sequence continues with `H` or with `T`. So we need a data type that branches off in groups of two…

There happens to be such a data type that is commonly used in Computer Science:

BinaryTree a = Node (BinaryTree a) a (BinaryTree a) | Null

This is, as the name suggests, a binary tree data structure. It is a recursive data type that is quite similar to a list. Each BinaryTree a has a type a, exactly like how each list [a] has a type a. Then, again like lists, each binary tree has two options:

-

Node (BinaryTree a) a (BinaryTree a): This is a node, having a single value in the middle and then two sub-trees, one on the left and one on the right. -

Null: A null value, representing the end of the tree.

This seems a bit complicated, so let’s look at a few examples.

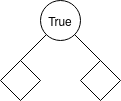

Possibly the most simply tree is: Node Null True Null. It would look like:

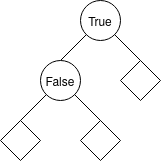

So the circles are nodes while diamonds are null. Another example:

Would be written like so: Node (Node Null False Null) True Null. Note how the left sub-tree is the one with the node value, not the right sub-tree.

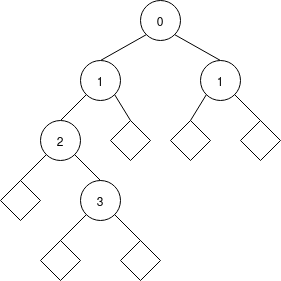

Let’s talk through another example, consider:

In Haskell: Node (Node (Node Null 2 (Node Null 3 Null)) 1 Null) 0 (Node Null 1 Null). As you can see, the haskell write-out gets rather complicated.

Now a bit of terminology, we call the top node, here it has value 0, the Root, just like the root of the tree. Also, Leaves are nodes that only have Null sub-trees. So in the last example, there are two leaves, one with value 3 and the other with value 1 and the right sub-tree of the root. Finally, Depth is the distance between the current node and the root. The value of the example above are the depth. When we refer to the ‘depth of the tree’, we mean the maximum depth.

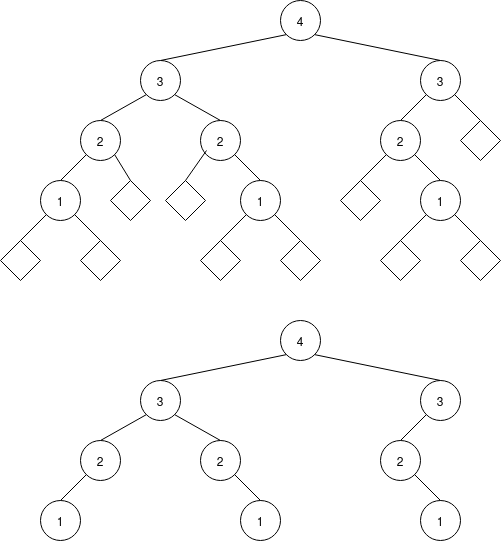

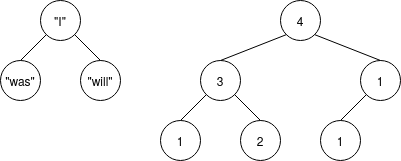

Of course, just like lists, trees can be as large and elaborate as you like. For example:

We have written the same tree here twice, leaving off the null nodes in the second version. We usually do leave off the null nodes.

Question: Draw Your Own Trees

Below we have written out two instances of Binary Trees. Draw each one:

Node (Node Null -5 Null) 10 (Node Null 7 Null)Node (Node (Node Null 'a' Null) 'b' (Node Null 'c' Null)) 'd' (Node (Node Null 'e' Null) 'f' Null)

Now we have drawn some example trees. Convert them to Haskell and write their type:

Tree Functions

Now that we understand the structure of a tree, let’s learn how to run functions on it. As said, it’s a recursive data structure just like lists, and hence defining a function for a tree uses recursion as well.

We will run through two examples of writing functions for trees.

Tree Functions: Leaves

Recall how we defined the function last for a list

last:: [a] -> a

last list = case list of

[] -> error "list in empty"

[x] -> x

_:xs -> last xs

Let’s attempt to define the same function for a binary tree. There is no one last element of a tree, so our goal is to find the leaves.

First we need to consider the type signature. We know that the function is supposed to take in a binary tree as input and we don’t have any constraint on the type of the elements of the tree, so let’s consider it be of type BinaryTree a. The output should be the list of all the leaves, so if the input is of type BinaryTree a, then the output has to be of type [a], as each leaf would be of type a.

Putting that all together the type signature of the function is:

leaves :: BinaryTree a -> [a]

Next we need to define the function. We know that an empty binary tree is Null and anything with at least one element is denoted by Node leftTree a rightTree. Given this, we have the cases:

leaves binaryTree = case binaryTree of

Null ->

Node leftTree a rightTree ->

So now let’s look at what the function is meant to be doing. We want the output to be leaves of the tree. So, when a sub-tree has pattern Node [] a [], then a is considered a leaf value. So we can alter the above to:

leaves binaryTree = case binaryTree of

Null ->

Node Null a Null -> [a]

What happens when the binary tree is Null? That indicates that the tree is empty and hence there are no leaves. So if that is the case, the output should be an empty list:

leaves binaryTree = case binaryTree of

Null -> []

Node Null a Null -> [a]

Currently, we have the base case of the leaves function. So now we move on to the recursion part of it.

Note how we used _ :xs -> last xs in last as the recursive case. We know that a binary tree has the following structure BinaryTree a = Node (left tree) (node value) (right tree). So, in this instance, we must recurse on both the left and the right sub-trees in order to generate all the leaves of the tree:

leaves binaryTree = case binaryTree of

Null -> []

Node Null a Null -> [a]

Node leftTree a rightTree -> (leaves leftTree) ++ (leaves rightTree)

We know the output of our function leaves is a list, so if we apply it to both sub-trees, we need to add the results back together. So, we need to use the ```++`` operator to concatenate the two lists.

As we haven’t used the node value a in the third case, it is good style to replace that with _:

leaves binaryTree = case binaryTree of

Null -> []

Node Null a Null -> [a]

Node leftTree _ rightTree -> (leaves leftTree) ++ (leaves rightTree)

And that is it! Putting it together, we get:

leaves :: BinaryTree a -> [a]

leaves binaryTree = case binaryTree of

Null -> []

Node Null a Null -> [a]

Node leftTree _ rightTree -> (leaves leftTree) ++ (leaves rightTree)

This function will find the leaves of any tree. For example, if we apply it to our third example binary tree, we get:

leaves (Node (Node (Node Null 2 (Node Null 3 Null)) 1 Null) 0 (Node Null 1 Null)) = [3,1]

So hopefully you can see that working with trees is exactly like working with any other haskell type: the same reasoning and logic applies, allowing us to make cool and interesting functions.

Tree Functions: Sum

Let’s analyse the thought process for another example: this time let’s calculate the sum of all the elements in a binary tree. If we were to calculate the sum of elements of a list, the function would be along the lines of:

sum:: (Num a) => [a] -> a

sum list = case list of

[] -> 0

x:xs -> x + (sum xs)

Let’s analyse step-by-step how to would write the function sum for a binary tree.

Again, let’s start with the type signature. Unlike the previous example,the type signature is pretty straight forward. All we have to do is add the values inside the tree. So, if the tree has type BinaryTree a, then the output is type a. Note though, that we must be able to add the type a, so we require it to be in the group Num:

sumTree :: (Num a) => BinaryTree a -> a

This is very similar to the type signature of sum .

Now that we have the type signature sorted, let’s look at the cases. Let’s start with the empty tree case. So what is the sum of an empty binary tree? Similar to that of an empty list the sum, it would be zero:

sumTree :: (Num a) => BinaryTree a -> a

sumTree tree = case tree of

Null -> 0

Now moving on to the recursive call, let’s consider the instance were we have Node leftTree k rightTree. Here the expected outcome is the k + (sum of all the values on leftTree) + (sum of all the values in the right tree). So the recursive call is on both sub-trees:

sumTree :: (Num a) => BinaryTree a -> a

sumTree tree = case tree of

Null -> 0

Node leftTree k rightTree -> k + (sumTree leftTree) + (sumTree rightTree)

Note how we don’t require the instance Node Null a Null as it is covered in Node leftTree k rightTree. This is similar to the list cases: we don’t need to specify x:y:xs in list recursion (unless the second element is needed), as the case x:xs already covers it. So, when it comes to trees, we have two main cases, Null and Node leftTree k rightTree, which cover all other cases, such as Node Null k Null , Node Null k rightTree and Node leftTree k Null.

So, we have finished our sumTree function:

sumTree :: (Num a) => BinaryTree a -> a

sumTree tree = case tree of

Null -> 0

Node leftTree k rightTree -> k + (sumTree leftTree) + (sumTree rightTree)

Question: Binary Tree Functions

- Write a function

treeNodesthat counts the total number of nodes in a binaryTree. For example:

treeNodes (Node (Node (Node Null 1 Null) 2 Null) 3 (Node (Node (Node Null 4 Null) 5 Null) 6 (Node (Node Null 7 Null) 8 (Node (Node Null 9 (Node Null 10 Null)) 11 (Null))))) = 11

- Write a function to calculate the depth of a tree. (See above for definition and example). For example:

treeDepth (Node (Node (Node Null 1 Null) 2 Null) 3 (Node (Node (Node Null 4 Null) 5 Null) 6 (Node (Node Null 7 Null) 8 (Node (Node Null 9 (Node Null 10 Null)) 11 (Null))))) = 6

- Write a

treeMapfunction that maps a function to all the values inside a tree. For example:

treeMap (+1) (Node (Node (Node Null 1 Null) 2 Null) 3 (Node (Node (Node Null 4 Null) 5 Null) 6 (Node (Node Null 7 Null) 8 (Node (Node Null 9 (Node Null 10 Null)) 11 (Null)))))

= Node (Node (Node Null 2 Null) 3 Null) 4 (Node (Node (Node Null 5 Null) 6 Null) 7 (Node (Node Null 8 Null) 9 (Node (Node Null 10 (Node Null 11 Null)) 12 Null)))

Advanced Trees

As you have seen above, binary trees qre quite useful, however, they are limited to each node having two children. So what if we want some nodes to have more than two children? We can’t do anything at the moment!

So let’s define a new data type with three children:

data TernaryTree a = Null | Node a (TernaryTree a) (TernaryTree a) (TernaryTree a)

So this TernaryTree types contains a value for the node and three more trees as children, defined similarly to BinaryTree.

However there are often circumstances that we don’t know how many children each node will have, for example if we were representing a file system on a computer, where each node is a folder. We don’t want to limit how many things we can put in the folder so we need a way to represent a tree with an arbitrary number of children for each node. In this case we store a list of children for each node. This is called a Rose tree and has a type definition very similar to the Binary Tree you saw earlier.

data Rose a = Rose a [Rose a]

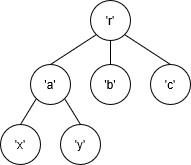

For example

would be represented by

Rose 'r' [Rose 'a' [Rose 'x' [], Rose 'y' []], Rose 'b' [], Rose 'c' []]

Question: Draw Rose Trees

- Now that you understand what a rose tree is, draw the rose tree corresponding to the following code representation:

Rose 15 [Rose 3 [], Rose 5 [Rose 1 [], Rose 3 [], Rose 7 []]]

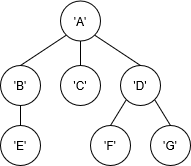

- Now write out the haskell code that would correspond to the following rose tree:

Question: Rose Tree Functions

Implementing functions that operate on rose trees is very similar to Binary trees, however, instead of recursing to the left child and right child, you will need to iterate through the entire list of children. With this in mind, implement the Binary tree functions you implemented earlier for Rose trees.

-

Implement

roseTreeNumNodeswhich takes a rose tree and returns the number of nodes. -

Implement

roseTreeHeightwhich takes a rose tree and returns the height. -

Implement

roseTreeMapwhich takes a function and a rose tree and recursively applies that function to every element of the rose tree.