What's in a heuristic?

Heuristics

While computers can’t understand what’s a “good” move intuitively, we can help them by giving them some rules to help their decision making. We call these rules ‘heuristics’, and they’re the same things that help you choose what move you want to make. Think about the sorts of play styles you might have; risky, safe, greedy, aggressive… these can all be emulated by defining different heuristics for your code to follow.

Take for example the classic Noughts and Crosses.

If it’s Nought’s turn where should the player place their token? Why? It’s an easy choice if you’re one move away from winning, but what if you’re not? A typical solution is to give a board state a ‘score’. This means that for any given move (which will produce a new board state) we’ll get a new board state with an associated score. By maximising your score each turn you should be making the best decision every step of the way.

Activity 1

Play backgammon with a friend, and think of the heuristics you use!

Rules

The objective is to move all of the pieces into the inner board, after which they can then be removed one by one from the board in what is called bearing off. The legal moves are as follows.

To start the game, each player rolls one die. The player with the higher number on their die moves first using the numbers shown on both dice. If both players roll the same number they must roll again. The players then alternate turns, rolling two dice at the beginning of each turn.

After rolling the dice, the player must move her pieces forward (towards the lower points) according to the number shown on each die, unless there is no such move possible. For example, if the player rolls a 3 and a 4 (written “3-4”, she must move one piece 3 points forward, and another or the same piece 4 points forward. The same piece can be moved twice, so long as both moves can be made separately and legally: 3 and then 4, or 4 and then 3. If the player rolls two dice the same, called a double roll, then that player must play the value of each die twice. For eample, a roll of “6-6” allows four moves of 6 points each. A player must move according to the numbers on both dice if it is at all possible to do so. If no move is possible then the player forfeits that move and the turn ends. If a move can be made according to either one die or the other, but not both, then the higher number must be used. If there is no move for one die, but its move is made possible by a move for the other die, then that sequence of moves is compulsory for that turn.

The destination point of each move must be:

-empty, or

-occupied by one or more of the player’s own pieces, or

-occupied by only one of the opponent’s pieces, called a blot.

Landing on a blot results in the opponent’s piece being hit: it is removed from the board and placed on the bar that divides the inner and outer boards. A player cannot move a piece to a destination point occupied by more than one of the opponent’s pieces; such moves are blocked. Otherwise, there is no limit to the number of pieces that can occupy a point at any given time.

Pieces placed on the bar must re-enter the board through the opponent’s inner board. A roll of 1 allows the piece to enter the board at the 24-point, a roll of 2 to the 23-point, and so on, up to a roll of 6 allowing entry on the 19-point. As above, a piece is blocked from re-entering if its entry point is occupied by two or more of the opponent’s pieces, in which case it remains on the bar. A player must re-enter all pieces from the bar before resuming movement of pieces on the board. Thus, if the opponent’s inner board is completely closed, with all six points occupied by two or more of the opponent’s pieces, then there is no roll that will allow the player to enter a piece from the bar. That player forfeits turns until at least one point numbered 19 through 24 becomes open.

When all of a player’s checkers are in their inner board (points 1 through 6) she begins bearing off. A roll of 1 allows removing a piece from the 1-point, a roll of 2 from the 2-point, up to 6 to remove a piece from the 6-point. If all of a player’s checkers are on points lower than the number shown on a particular die, then that move can be applied to bear off one piece from the highest occupied point. The player can also move a lower die roll before the higher even if that means the full value of the higher die is not fully utilised. As before, if there is a way to use all moves showing on the dice, by moving checkers within the inner board or bearing them off, then the player must do so.

The first player to bear off all of their pieces is the winner of the game.

Dice rolls introduce an element of luck into the game. While the dice may determine the outcome of a single game, the player with the better strategy will usually come out ahead of weaker players over multiple games. For this reason, matches comprise a number of games (e.g., best of three, or best of five).

Activity 2

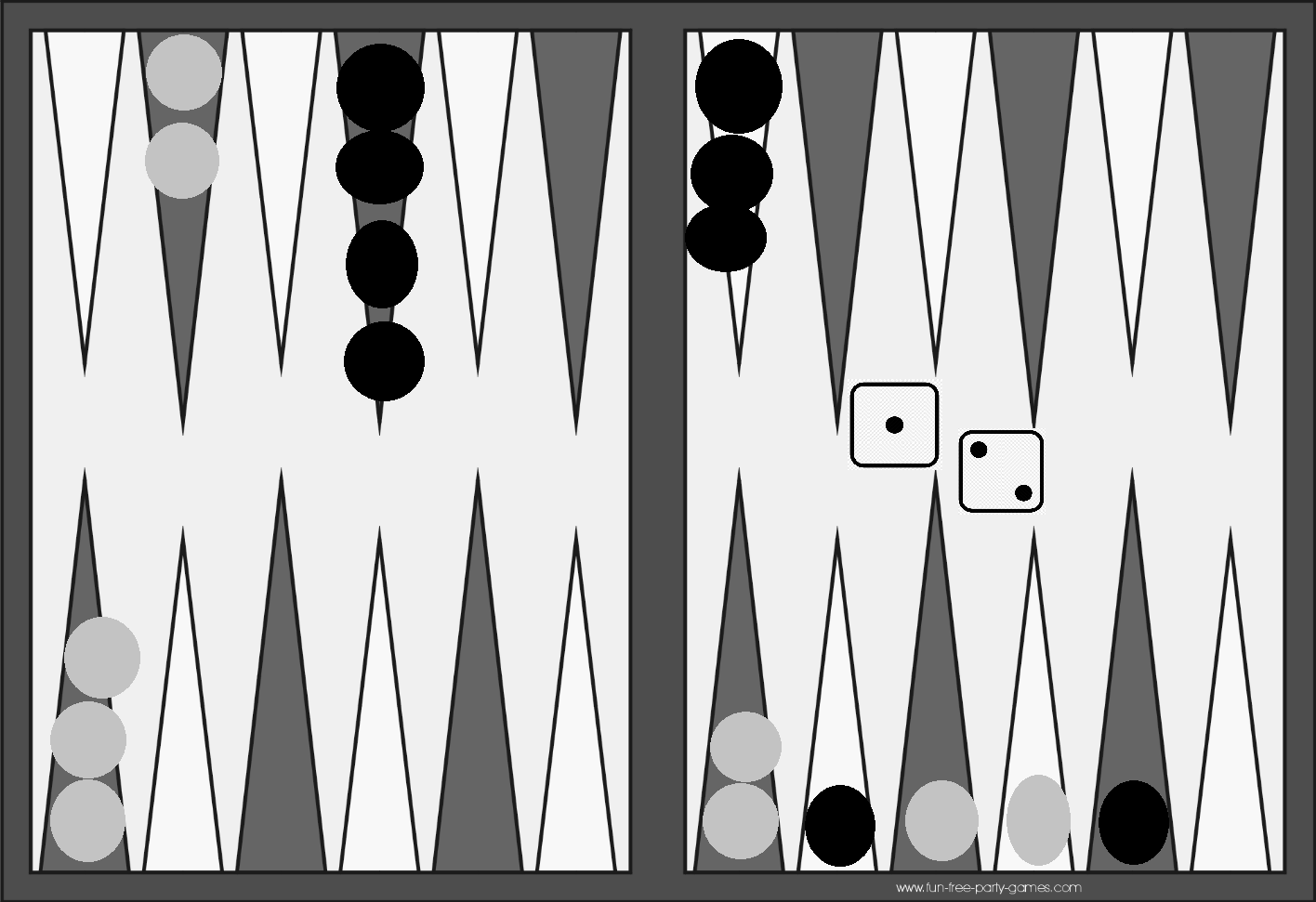

Have a go at applying your heuristic to this sample board state. Play as Red (Grey in this picture) and move to the bottom right.

- Convert this board to the data type in the assignment

- Generate all valid moves for the given dice rolls

- Apply your heuristic to each move and pick the highest one.

Activity 3

In this activity, we see how the Board and State data type is implemented in the assignment. This is critical for understanding the game and writing functions that can use them.

Definitions

First, remember how they are defined:

type Point = Maybe (Player, Int)

data Board = Board {

points :: [Point],

wBar :: Int,

bBar :: Int

}

In groups, discuss how the Board type relates to the game. Which data elements relate to a specific player? Which relate to the general game?

data State = State {

status :: GameStatus,

board :: Board,

turn :: Player,

movesLeft :: [Int],

wPips :: Int,

bPips :: Int,

wScore :: Int,

bScore :: Int

} deriving (Show)

data GameStatus = Playing | Finished

deriving (Eq, Show)

In groups, discuss how the State type relates to the game. Which data elements of relate to a specific player? Which relate to the general game?

Drawing a Board

Now that you understand the data types, envisage a board in the middle of a game. Draw the board and then outline the equivalent data instances.