Pal Plays Sushi Go

PAL Plays Sushi-Go

Overview

Over the past 10 weeks, you have learnt a lot of different concepts in computer science and how to implement these in Haskell. For assignment 3, you will need to pull together many of these concepts to build a bot that will play Sushi-Go!

Instead of immediately leaping into buildign a bot, let’s break down the steps that are reqiured:

1) Sushi-Go Game: First and foremost, we need a way to play Sushi-Go on the computer. This is mostly just converting game-logic into functions and data that represent that logic. 2) Game Tree: Before we begin building a bot, we need a method to look ahead at what could happen; the best way to do this is to generate a game tree. 3) Minimax: With our game tree, we can use minimax to evalute what the best possible future position will be. We can then make a bot that will select the move that will lead to that future game state. 4) Heuristics: We need our bot to be smart and evalute the game states intelligently. To do so, we need to develop a set of heuristics that accurately guess how good a position will be. 5) Alpha-Beta Pruning: Our bot is fully functional now, but it is wasting a lot of time evlauting game states that will never be considered. So we can make it much faster and thus better by preventing this time loss.

There are a lot of steps there and it may seem like quite a daunting task. However, there a few good bits of news. Firstly, for your assignment, Ranald and the tutors have already implemented the Sushi-Go backend. This saves us a lot of time! Secondly, many aspects and steps have been covered very thoroughly in lectures and labs. So if you ever do get stuck, look through the lecture slides and code and you may just find the answer (maybe even in Haskell code!) right there. Finally, PAL is here to help! This session we are going to go through steps 2-5, explaining what is happening and how it happens. So let’s go started!

Generating the Game Tree

Given that we have a back-end, we start at generating the game tree. Recall that a game tree is simply a normal tree with game states as the nodes and the layers of the tree being the turns. Usually, as mutiple possible outcomes can happen each turn, a game tree is represented by a Rose Tree.

To generate a game tree, we will need to make a few assumptions about types and functions. We are not going to do the assignment in PAL (sorry we are not allowed!), so we are instead going to make the follow general types:

Type a = # State of the Game #

Type b = # Moves of the Game #

With these, we can make the following functions:

legalMoves :: a -> [b]

legalMoves state = # RETURN LIST OF POSSIBLE MOVES FROM STATE #

nextState :: a -> b -> a

nextState state move = # RETURN STATE THAT FOLLOWS FROM APPLYING MOVE TO STATE

We are not going to look into writing these functions. That is because they rely too heavily on the specific back-end being used to really be informative. So when you try write these functions, look through the assignment spec and the code written already written.

We are going to look at the next step of using these functions to generate the tree. Simply we want the following function:

generateTree :: Int -> a -> (a -> [b]) -> (a -> b -> a) -> RoseTree a

generateTree depth initialState legalMoves nextState =

# RETURN GAME TREE WITH CERTAIN DEPTH #

Try write the function yourselves; it should be a simple recursion once you unpack it all!

Minimax

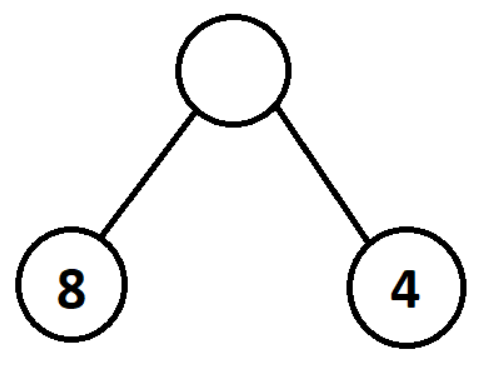

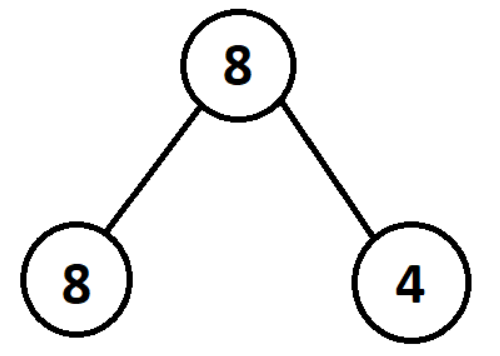

Minimax is an algorithm that you can use to evaluate the best possible move to make for a given game tree. The algorithm relies on using some heuristic function to evaluate the end board states (the leaf nodes of the game tree), and passing these values up the tree to find the best move. As an example, take this simple game:

If we are wishing to maximise the score for the root node, then we compare the values of all the children, and choose the maximum to “pass” up to the parent node.

The parent node now contains the value of the best result of its children. This process is then repeated for all nodes, alternating beetween maximising and minimising at each level, until the entire tree has been completed. We alternate between maximising and minimising to represent the alternative turns between you and your opponent: your opponent is going to choose your worst game state!

1) Using a diagram, perform a Minimax algorithm on these balanced binary search trees with the following terminal node pairs:

(-2, 4) (15, 0) (3, 11) (-7,-9)

2) Create a Minimax function with a lookahead value of 1 (look one turn into the future). 3) Write a general Minimax function that works for a certain depth:

minimax :: RoseTree a -> Int -> a

minimax tree depth = # RETURN BEST LEAF NODE #

Heuristics

So what is a heuristic? Well suppose we have a game state and we want to know how well Player 1 is doing in this game state: the heuristic evaluates this game state and outputs a score. The higher the score, the better Player 1 is doing.

So we will use heuristics to evlaute the leaf nodes in minimax. This will make the bot choose the moves that will lead to game states that is is more likely to win from.

But what are some heuristics? How do someone make one? Well let’s look at some examples. Here we use the game chess as our game:

- How many pieces Player 1 has on the board?

- What is the difference of in the total scores of the pieces between Player 1 and Player 2?

- How many “good” pieces does Player 1 have left?

- How many possible moves can Player 1 make (i.e how open is their position)?

Now it is your turn! Try come up with some more heuristics for chess, or another game if you wish. One you have a 5 or so, choose two and write them in Haskell - you may assume that you have a nice back-end that gives you the information needed about the game state.

Alpha-Beta Pruning

Currently our bot is fully functional: it looks into the future of the game and chooses the move that will most likely result in it winning. However, it is wasting a lot of time in minimax by evaluating tree branches that will never be used. We can fix this, and so make the bot faster and able to search to greatre depths, if we implement alpha-beta pruning.

Basically, the alpha-beta uses two values, alpha and beta, which are the minimum score that the maximizer holds and the maximum score that the minimizer holds respectively. Initially, alpha is negative infinity and beta is positive infinity. When the maximum score that the minimizer holds becomes less than the minimum score that the maximizer holds (i.e. beta ≤ alpha), the maximizer doesn’t need to consider further children of this node, as they will never be reached in the actual play. And thus we could cut these unreached decision subtrees and the search will be optimized!

That is quite confusing, so let’s look at some examples:

1) Perform the alpha-beta pruning on this minimax tree:

2) Once you are confident enough with using alpha-beta prunign youself, try implement the function in haskell!