Tree Huggers

Tree Hugging for Dummies

Jay and Tina are back and greener than ever after the mid-sem break. After splurging at Pitt St Mall in Sydney, the nearest big city, they realised how wasteful their current lives were and had a sustainability epiphany.

With heavy suitcases and heavy hearts, they sought to reconnect with nature. Their first main goal: learn how to understand trees.

List comprehension

Before they can understand trees, they must first understand the root of the problem. Lists are fundamentaly the same as trees and a mastery over lists provides a strong foundation for understanding trees.

List comprehensions allow us to define functions over lists in a beautifully concise form. They are basically a combination of the higher-order functions map and filter.

As a template, list comprehensions are defined like so:

[elements with function applied, where elements are drawn from list with conditions]

There can be one or more conditions, or even no condition!

[elements with function applied | elements <- list, condition, condition, etc...]

| This ‘ | ’ in the middle is known as the generator, as it generates the elements that we want the function applied to. Generators need to come before the conditions, as the element(s) is/are out of scope otherwise. |

[ x + 2 | x <- [1..10] , isEven x]

= [4, 6, 8, 10, 12]

This will add 2 to every even number between 1 and 10.

[ x + 2 | x <- [1..10] , isEven x, x > 5]

= [8, 10, 12]

This will add 2 to every even number between 1 and 10 which is greater than 5.

Which do you think happens first - the map or the filter? Discuss. (Hint: think about the generator.)

Can you figure out a way to output [6, 8, 10, 12]?

Let’s have some practice

- Write a function that doubles each element in a list of integers

- Write a function that returns a list of tuples of two input lists

- Write a function that capitalises each letter in a string

You’re likely to have already written some of these functions, however here we would like you to construct them using list comprehension. (If you get stuck though, or are a bit rusty, feel free to try using higher order/in-built functions first!)

Extension question (optional)

What is the result of this expression?

foldl (&) blank ([drawTileAt (x, y) | x <- [-10..10], y <- [-10..10]])

Protip: you should remember this from Assignment 1.

Tree growing crash course

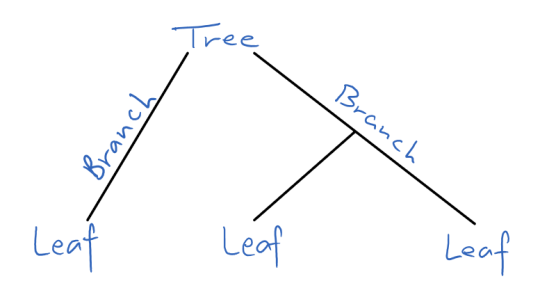

How it’s set out:

What it looks like:

Trees are a data type used in computer science as an organisational structure (and they’re something you’ll be seeing a lot of in your 2nd assignment!). However, trees in computer science grow downwards!

In Haskell, this is defined as follows:

data B_Tree a = Node a (B_Tree a) (B_Tree a) | Empty --Binary tree data type

data Rose_Tree a = Rose_Node a [Rose_Tree a] -- Rose tree data type, what does it mean?

In essence, this defines a tree as either null (containing nothing) or as a node with left and right branches, which lead to either a null (the branch is a dead end!) or another node (the tree is extended) type. Subsequently, each node of this tree would recursively also be defined this same way.

The tree seen above is an example of a Binary Search Tree (BST). A binary search tree has its elements ordered from least to greatest, left to right. Each point in the tree is known as a node containing a value , where the value in each node must be greater than or equal to any key stored in the left sub-tree, and less than or equal to any key stored in the right sub-tree. This ordering can be numerical, alphabetical, etc.

BSTs are extremely helpful in efficiency in the lookup, addition and removal of items due to its binary, rather than linear, nature.

Lists to trees

Draw up the binary trees that would result from creating a tree out of the following lists: (Use the first value as the top of the tree)

[2, 3, 56, 3, 6, 2, 1, 67]["Apple", "Oranges", "Banana", "Pineapples", "Peach", "Apricot", "Kiwifruit"]- [0, 01, 10, 11, 100, 101, 110, 111]

Trees to lists

We can convert trees to lists by “flattening it. Have a think about how this could be defined using the Tree data type given above. Type signature is given below:

treeFlatten:: Tree a -> [a]

Challenge question (optional)

Have a think about how you would write a function to map over a tree, that is, how to define the higher-order function map but for the tree data type specifically.

Hint: the type signature is given below:

mapTree :: (a -> b) -> Tree a -> Tree b